Journalists, Stop Saying “Against Their Will” — It’s About Care, Not Force

Last month in NYC, a woman was set on fire and burned to death on a subway train in Brooklyn.

The victim, Debrina Kawam, 57, had spent time in a homeless shelter in NYC. Did she have substance abuse issues? According to the New York Times, she did. Mental illness? No official word yet, but it often pairs with substance abuse.

In any event, if she had been placed into treatment, even “against her will,” she would probably be alive today.

Sebastian Zapeta, 33, is accused of starting the blaze with a lighter while Ms Kawam was asleep. He allegedly fanned the flames with a shirt and then watched the fire grow from a bench outside the subway car.

Mr Zapeta claims to have no memory of the incident. He says he had consumed a lot of alcohol. Hmmm.

These and other recent subway crimes have prompted NY Governor Kathy Hochul to announce plans to spend $1 billion to revamp care, and strengthen New York's involuntary commitment laws.

According to CBS News, “she also called for making changes to Kendra's Law, which provides court-ordered outpatient care for people who are at risk to themselves, or others.”

Yes, please.

I have a beef, though: please stop using the phrase “against their will” when talking about getting those with mental illness into treatment.

When people like my son are symptomatic, their “will” is seriously flawed. They’re often psychotic, which means they have a defective or lost contact with reality.

Again, I ask: if someone with Alzheimer’s disease refused help, would you just let them wander around?

The other word I have issue with is “dangerous” when describing those with mental illness. I hear that a lot, and it’s, at best, incomplete.

Why do we so often describe those with psychosis as “dangerously mentally ill”? That was the description I heard on the radio yesterday along with the phrase “against their will.”

Are they dangerous? Yes, sure, sometimes, But. more likely, they are vulnerable -the “vulnerable mentally ill.”

NYC - Above Ground

People like Debrina Kawam. People like my son.

A few weeks ago, I wrote about how my son, Ben, was soon to be homeless. Well, he isn’t, yet, because he refuses to move out of his affordable housing.But he will soon be evicted, unless we can get him to “come to his senses” and find another place to live.

Come to his senses? Ha! That is precisely the problem.

Ben is refusing treatment, He is often high, or worse. He has stopped his meds. And, because of that, he has become a victim. He is committing no harm to others, but has been forced from his apartment by dealers who have taken it over and “allow” him to sleep on his own couch, probably in exchange for drugs.

My son no longer asks me for money. He doesn't ask for help. He doesn’t ask for anything.

He just spends all day at a clubhouse for the homeless, eating free meals, listening to loud music on his headphones, keeping to himself. Then I guess he goes home to sleep on his couch…while he still has one.

“Dangerous? Sometimes, But. more likely, they are vulnerable -the ‘vulnerable mentally ill.’”

This is a person who, five short years ago, was a full-time restaurant server with 5-star reviews, driving a Lexus, paying taxes. Then Covid came, marijuana followed, and he broke down.

Is he okay? No!

Does he think he is okay?

Sadly, yes.

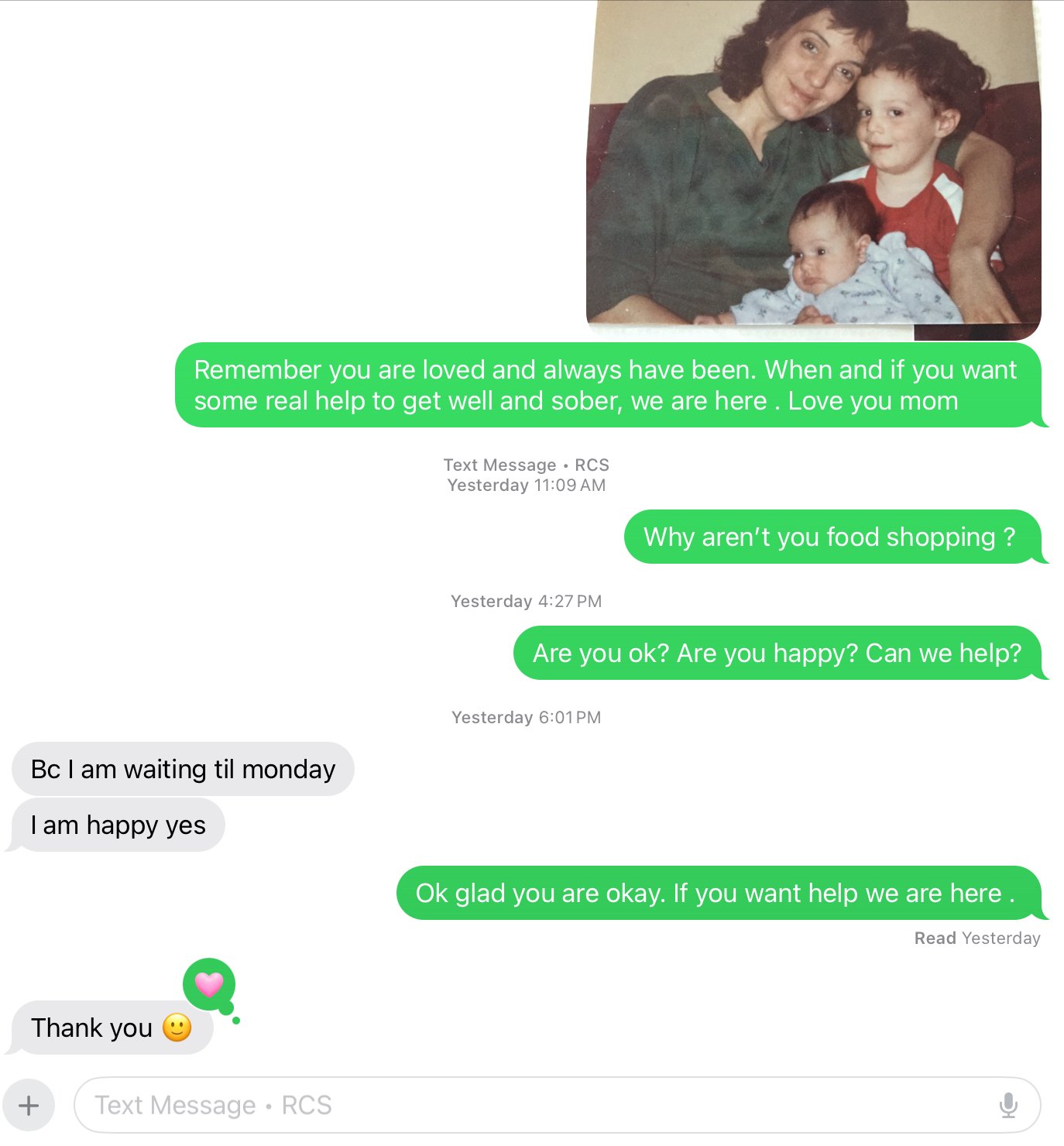

See this text exchange from yesterday:

text exchange of love, hope and lack of insight

No, my son is not okay. He just hasn’t been hurt badly enough yet to qualify for treatment.

What does it take?

In stories about efforts to address homelessness—especially when severe mental illness is involved—the phrase "against their will" is repeated like a drumbeat. It’s a phrase that carries weight, evoking images of force, violation, and a stripping away of autonomy. But it's also a phrase that simplifies, distorts, and ultimately misrepresents the reality for so many vulnerable people.

When someone is experiencing a severe mental health crisis—living unsheltered, disconnected from reality, and unable to meet their most basic needs—their will isn't always clear, consistent, or capable of prioritizing their own safety. Mental illness can cloud judgment, distort perceptions, and create deep mistrust, even toward those trying to help - like their case managers, or their family.

Journalists, with their power to shape public opinion, need to be careful with the words they choose.

"Against their will" suggests a struggle between personal freedom and intervention. But what if we reframed this? What if we recognized that leaving someone to suffer on the streets, untreated and exposed, isn't an exercise of freedom—it's neglect.

“No, my son is not okay. He just hasn’t been hurt badly enough yet to qualify for treatment.”

And it’s not just about danger. Too often, media narratives focus on whether someone poses a risk to others. But vulnerability is its own emergency. A person shivering on a sidewalk in winter, malnourished, delusional, and isolated, doesn’t need to be dangerous to deserve care—they need to be human. They are vulnerable.

My son is one of these people. Today, he tells me he's fine, happy, and doesn't need help. But five years ago, while in treatment, he was gainfully employed, contributing to society, and connected to his family. He was genuinely happier. Now, he believes he’s okay, but he’s not. His reality is distorted by an illness he cannot see, and his refusal of care isn’t a sign of independence—it’s a symptom of his condition.

This isn’t about stripping away rights. It’s about recognizing that dignity includes access to shelter, treatment, and a chance at stability. It’s about understanding that severe mental illness can impair someone's ability to make informed decisions about their own care. It’s about seeing intervention not as coercion, but as compassion.

About a year ago, we interviewed Brian Stettin, senior advisor on severe mental illness to NYC Mayor Eric Adams, on our podcast, Schizophrenia: 3 Moms in the Trenches. We will do a follow-up interview this month, but at that time Brian was talking about how enforcing Kendra’s Law has helped people reconnect with their families, get off the streets, find life again. All, initially “against their will.”

So, to journalists: Please reconsider the phrase "against their will." Instead, talk about support, care, and connection. Focus on the vulnerability that makes intervention necessary, not just the potential for harm.

Words matter. And in this case, they could make the difference between reinforcing stigma and building understanding.